The history of the Eichelhütte

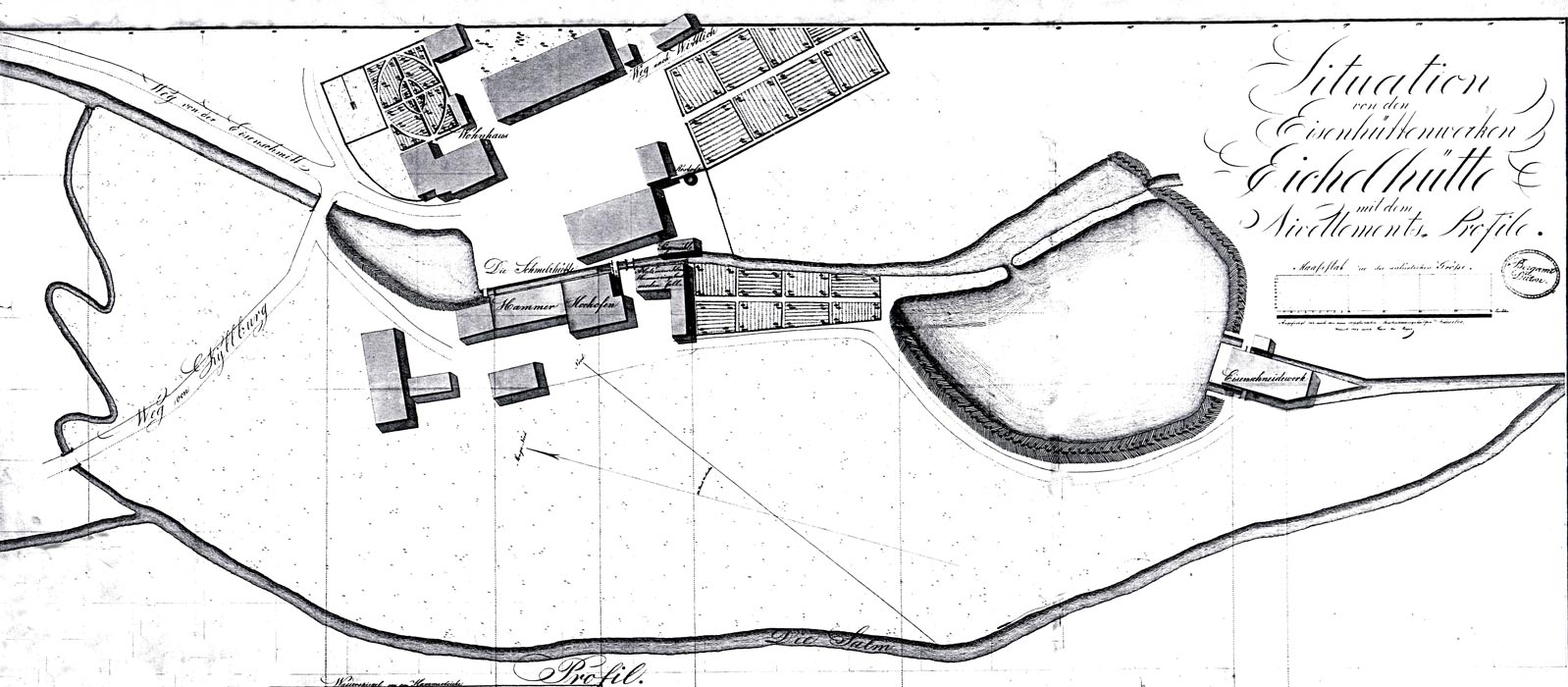

In the middle Salmtal, Johann von Minden, bailiff of the Meer- and Bettenfeld lordship, acquired a stone hut area from the Himmerod Abbey on June 8, 1701. He received about 3 acres in order to build a foundry hut, hammer, punch mill, coal shed, mold house and house at his own expense. In 1704 he sold the steel works, the foundry, the hammer and the stamping mill to Franz von Pidoll, the owner of the Quint works near Trier.

Pidoll then shaped the development of the Eichelhütte for a full century. The location was favorable as there was sufficient hydropower and wood available. The water power of the Salmbach could drive hammers and blowers via water wheels. Two rolling mills were built in Eichelhütte. In the upstairs factory, band iron, which had a high degree of toughness, was preferably produced. A cutting and sheet metal rolling mill was also operated in the lower plant, in which wrought iron and black plate were produced.

Under the influence of the French Revolution in 1802, the iron and steel works in Eichelhütte passed to the French Johann Stephan Marcellin. Marcellin had the Eisenschmitt forest cleared vigorously, which caused great damage to the community.

The Krämer brothers acquired the hut in 1820/1821. They had bought the whole Eichelhütte, with a blast furnace, an overshot water wheel, two large hammers, a small hammer, a rolling mill, a sawmill with four fires and six water wheels, one of which was by the furnace and the other a quarter of an hour above and the name Eisenschmitt (the original hut place) led, also with a cutter with two undershot water wheels. In 1840, 182 workers in Eichelhütte produced 8,000 quintals of pig iron, 3,000 quintals of bar iron, 2,000 quintals of wrought iron and 60 quintals of small iron. If the lower plant (the location of today’s Molitors Mühle) in Eichelhütte had already been shut down in 1860, the large forests prompted the owner Krämer to build a sawmill in the upper plant (the location of today’s factory building) in 1863. In 1868 the plant in Eichelhütte was completely shut down. This was mainly caused by the lack of a rail link. But other reasons may also have played a role, such as the fire in two blast furnaces in Eisenschmitt and the boom in industry in the Ruhr area.

Acquisition of the Eichelhütte by Nikolaus Molitor – 150 years ago!

Peter Molitor writes in his chronicle: “Now the question arose as to what brought my father Nikolaus Molitor, son of the miller from the Upper Molitors mill in Schweich, to Eichelhütte? Standing on bare feet, he visited his bride in Oberkail in the spring of 1870. There he learned that the so-called sheet metal rolling mill in Eichelhütte was available for sale. Since Nikolaus Molitor, like most Molitors, was a miller but did not yet have a mill, he was very interested in the matter. So he immediately set off with his future brother-in-law Peter Kuhn to find out whether the building and the water power were suitable for a mill for Müller. He found an empty factory building with a seven meter high and about 1.20 meter wide cast-iron water wheel, a forge (blacksmith’s hearth) with a 30 meter high chimney, the 2 acre pond and a 4 acre adjacent meadow. So they found out that this system was probably suitable for the installation of a mill and that the whole Eichelhütte belongs to the hut owner Kramer from Quint.

My father didn’t think twice about it, went straight to Quint and on July 6, 1870, bought the plate rolling mill with water wheel.

His intention to start preparations for installing the mill immediately was thwarted by the outbreak of war in June 1870.

After his discharge, he was able to set about manufacturing the things necessary for the mill equipment at full speed. His skills in woodworking, which would have done many a carpenter credit, came in very handy. He did all the woodwork without the help of a mill builder. His brother Matthias, who had set up a locksmith’s shop in Schweich, took over the production of the necessary shafts, bearings, mill iron and all the locksmith work. Setup and construction could be accelerated so that it was possible to put the mill into operation on June 1, 1871.”

The first electric light in Molitors Mill – 130 years ago!

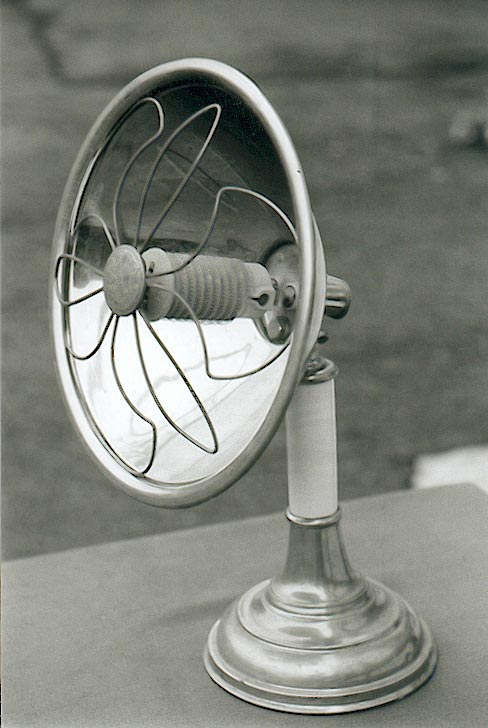

In 1878 King Ludwig II of Bavaria had the Venus Grotto in Linderhof Palace electrically illuminated. The plant was built by Sigmund Schuckert and is considered the first permanently installed power plant in the world. The world’s first electric power plant that produced electricity for the public was built in 1881 in a small town in England called Godalming. A Siemens electric generator was powered by a water wheel. Street lamps were lit with the electricity generated. The first German block station was put into operation in February 1882 by Paul Reisser from Stuttgart with electricity for 30 light bulbs. Edison founded the Edison Electric Illuminating Company in 1880 with the aim of supplying New York City with electricity. On September 4, 1882, Edison flipped the switch. The first German power plant in Berlin’s Markgrafenstrasse was put into operation on August 15, 1885. This enabled public roads to be illuminated within a radius of 800 meters and electrical energy to be given to everyone for a fee. In West Germany, the first public power supply began in Barmen and Elberfeld in 1886. In 1888 a son of Nikolaus Molitor, Claus Molitor and his friend Wilhelm Feuser from Eisenschmitt took up these developments. The first electrically generated light shone in the Molitors Mühle on February 25, 1889. The public power supply followed in Düsseldorf in 1891. In Heilbronn (Lauffen), the first large electric hydropower plant was inaugurated in 1892. Dortmund followed suit in 1897, and Bochum from 1898. In 1898, Altenessen, which is now part of Essen, started up a small steam power station. On April 25, 1898, the Rheinisch-Westfälische Elektrizitätswerk A.G. Essen (RWE) founded. The power plant was put into operation in 1900 with a machine output of 1200 kilowatts. So we were one of the first to have electric light in THIS house!

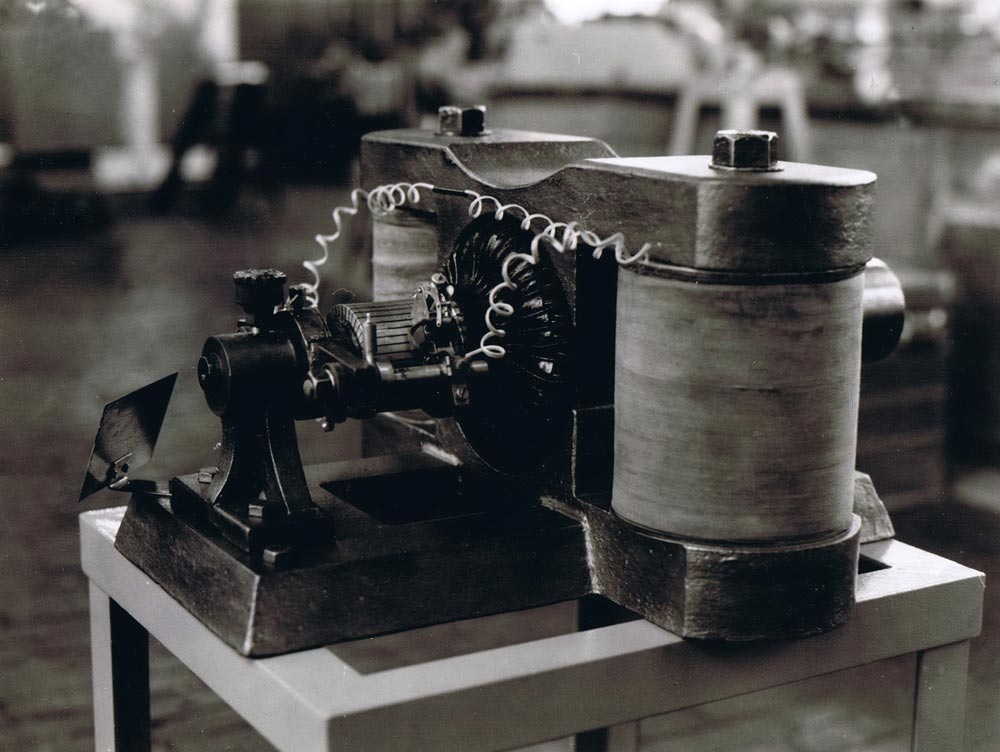

As a contemporary witness, Peter Molitor reports on the activities of his younger brother Claus in the Molitors mill: “It was in the spring of 1888 when Matthias Arenz, who at that time lived in Eichelhütte and ran his leather black factory, brought his nephew Wilhelm Feuser, who was an accountant in Cologne, home to take over his bookkeeping. Feuser, a neighbor of ours, was often our guest on Sundays. In the course of the conversations he often spoke about the fact that in Cologne, together with a friend who wanted to become an electrician, he had often made experiments in the then little-known field of electricity. As far as his free time allowed him, he was always present at these interesting experiments and he would like to continue working in this area. First he wanted to try to build a dynamo machine. To do this, he needs a specialist to produce a wooden model. After this, a cast should be made for the dynamo housing. My father, who was very good at woodworking, agreed to make the model from a drawing. The casting was completed at an industrial company Dutscher in Luxembourg and construction could soon begin. That was easy to say, but on closer inspection it wasn’t that easy, you were pretty much groping around in the dark. Winding the magnet was easy, but making the armature was more difficult, e.g. the number of coils, the correct wire size, etc. The most difficult part was making the collector. There were no cast slats. At that time, these had to be cut off from a brass rod and filed to the correct cone, all work for a trained specialist, but who was missing. As a young bookkeeper Feuser had hardly any tools in hand and was not in a position to carry out the work necessary to set up the dynamos in practice.

That was the moment my brother Claus had been waiting for, so to speak, because outside helpers shouldn’t be called in and let in on the plans. Claus, who was not yet fifteen at the time, who had already tinkered with all sorts of things as a schoolboy, including A small sawmill with a sawmill working on it, which was put into operation by a water wheel from the water pipe, was enthusiastic about the work and agreed to carry out the same according to Feuser. My father, not entirely convinced that Claus could do this, let him have it, and I must say it worked, if not always at first glance. After a few weeks of intense activity, the machine was ready for an attempt to be made. We were of course excited about the result like a fiddle. And then one day when the belt was put on, the machine remained obstinate. It was already running quietly, but there was no electricity. The experiments carried out then did not change this fact either. Now Holland was in need. What was to be done? What was the mistake? After some back and forth, it came to the conclusion that there must be a design flaw. After this failure, many would have thrown the gun in the grain. Not so my father and even less so the two “mechanical engineers”. It was decided to try again immediately. So first of all a new model and a new cast had to be procured, and when the new housing was available, the construction began immediately, and I would like to say with even more enthusiasm than with the first machine. After weeks of busy activity, it was finally time again that a new attempt could be made. Again the tension was great, but this time it worked.

It was on February 25, 1889, when three light bulbs in the kitchen, mill and living room shone with self-generated electricity, generated by a self-made dynamo, this operated by a drive belt in the mill and thus ultimately by the water of the Salm. Eichelhütte thus pioneered the spread of electricity. Interested parties came from everywhere to see this miracle. That was a sensation back then. As a precaution, we only installed these three lamps for this experiment, but after we had determined the advantages of electric light, the light pipe was laid through the whole house, from the basement to the attic. It soon turned out that the machine did not have enough power to power the lamps required. That was the moment that met my brother Claus’s wishes. With the consent of my father, the then sixteen-year-old set about building a much more powerful machine. Because he had done the practical work on the first two machines, building a larger one was no problem for him. He could be satisfied with the success. The second machine fed up to 25 lamps from 1891 and was a light source for decades. “(Today the dynamo can still be viewed in the Hotel Molitors mill).

The first holiday guest in the Molitors Mühle – 100 years ago!

It was 1917 when Ms. Backheuer from Berlin wrote to her wine supplier in Brauneberg asking for accommodation: “The famine in Berlin is great and she doesn’t want to be starved to death in Berlin.” Ms. Backheuer immediately opened up for the answer from Brauneberg the way. When she arrived in Brauneberg, Ms. Backheuer gave the reason for her appearance again. Anna Mertes, the wine supplier from Brauneberg, replied: ‘Dear Frau Backheuer, you can live here and drink wine, but we don’t have much to eat ourselves. I’ll make you a suggestion. Go to my daughter Katharina Molitor in Eichelhütte, there you have a farm, a mill and enough to eat ’.

The very next morning, on June 5, 1917, Ms. Backheuer set off. She arrived at Eichelhütte before lunch. To Katharina Molitor she said: “I’m Ms. Backheuer and I come from Berlin. Your mother sends me to you with the request to take me in. ”She repeated the words that she had already uttered in Brauneberg. Frau Backheuer was received with pity, not knowing that she would be the first guest and with her the beginning of a pension and later a hotel.

The beginning of the guesthouse

On her first walk, Mrs. Backheuer met two walkers who came from Elberfeld and lived as guests in Eisenschmitt, but were not satisfied with the food. Frau Backheuer brought these ladies to the mill. They too were accepted. The same game was repeated for a few days, and before the Molitor family knew it, the number of guests had risen to seven. So it happened that Molitor’s mill unintentionally became part of the catering trade. In the first summer 19 guests came to us in this way, in the second year in 1918 there were already 58 guests. On August 16, 1918, a servant’s carelessness burned down the shed. Actually, father wanted to rebuild the shed in autumn, but at the last moment came up with the idea of building a guest house instead of the shed. In the spring of 1919 the plan was put into practice and by 1920 we were able to accommodate 14 more guests in the new building. All rooms were equipped with cold running water. In addition, there was a bathroom for the guests with a wood-fired water boiler and a communal toilet with a flush. We have had electric light in the whole house since 1889.

The decision

It was a matter of course for the mill residents and farming families to buy their own produce as much as possible. We kept potatoes in the field, vegetables in our own garden, pigs for slaughtering for sausage, meat and ham in our own production, cows for milk, butter and quark and their meat, used chickens for daily fresh eggs, good chicken soup and for roasting. Grains such as rye and wheat were grown for baking bread. The oats in the fields were for the horses, the hay from the meadows, the racks from the fields and the meal were for the cattle. The large garden with vegetables and fruit could feed the family and guests. This was particularly appreciated, especially in difficult times, when the famine was great during and after the wars.

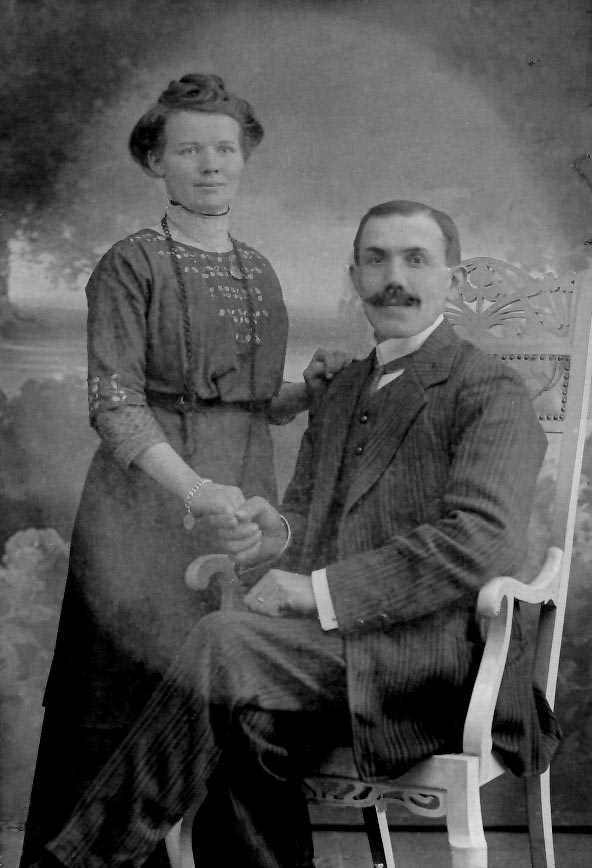

Now the Molitors Mill actually had three businesses at the same time: a grain mill, a farm and a guesthouse. There was a lot to do everywhere. Walter was intended by his parents to be the heir of the mill. In the winter months 1951-1952 he attended the master class in Wittlich every Saturday. The flour wagon drove weekly on Mondays and Thursdays to Oberkail, Schwarzenborn, Gransdorf, Seinsfeld and Steinborn and every 14 days to Kyllburgweiler. Deliveries were made to customers in Eisenschmitt on Tuesday afternoons. In order to pull the wagons full of sacks of flour up the steep Salmberg to Schwarzenborn, our two horses had to use all their strength. From there it went over mountains and valleys to Oberkail, Seinsfeld, Steinborn and Kyllburgweiler. But it came to an end with a general mill death, which was also triggered by the large electric mills, against which one could no longer work economically. Until the mill was shut down on January 1, 1957, Walter Molitor worked as a master miller with his mother Katharina in the mill. Then Walter married his wife Elfriede Molitor, b. Hoppe from Lippstadt on May 8, 1957. They decided to invest in gastronomy and, in addition to the mill, also to dissolve the farm.

The first conversion of the new Molitors mill

It was planned and considered. There were two different heights to consider, the height of the pond and the courtyard level, between which there was a height difference of about three meters. Dr. Hans Simon, owner of the Bitburger brewery, was often our day guest. In pleasant conversation we got the idea that we intend to expand and modernize the hotel. Then Dr. Simon’s answer: “For this historic project I can only recommend the architect Bert Emmerich from Bitburg, because with him you are in good hands”. (Mr. Emmerich was his architect in the Bitburger brewery at the time). The precise planning of the renovation with the architect Emmerich was of great importance. It started two years before the first phase of construction began. So we were able to cut the wood that we needed for the first construction phase from our own forest.

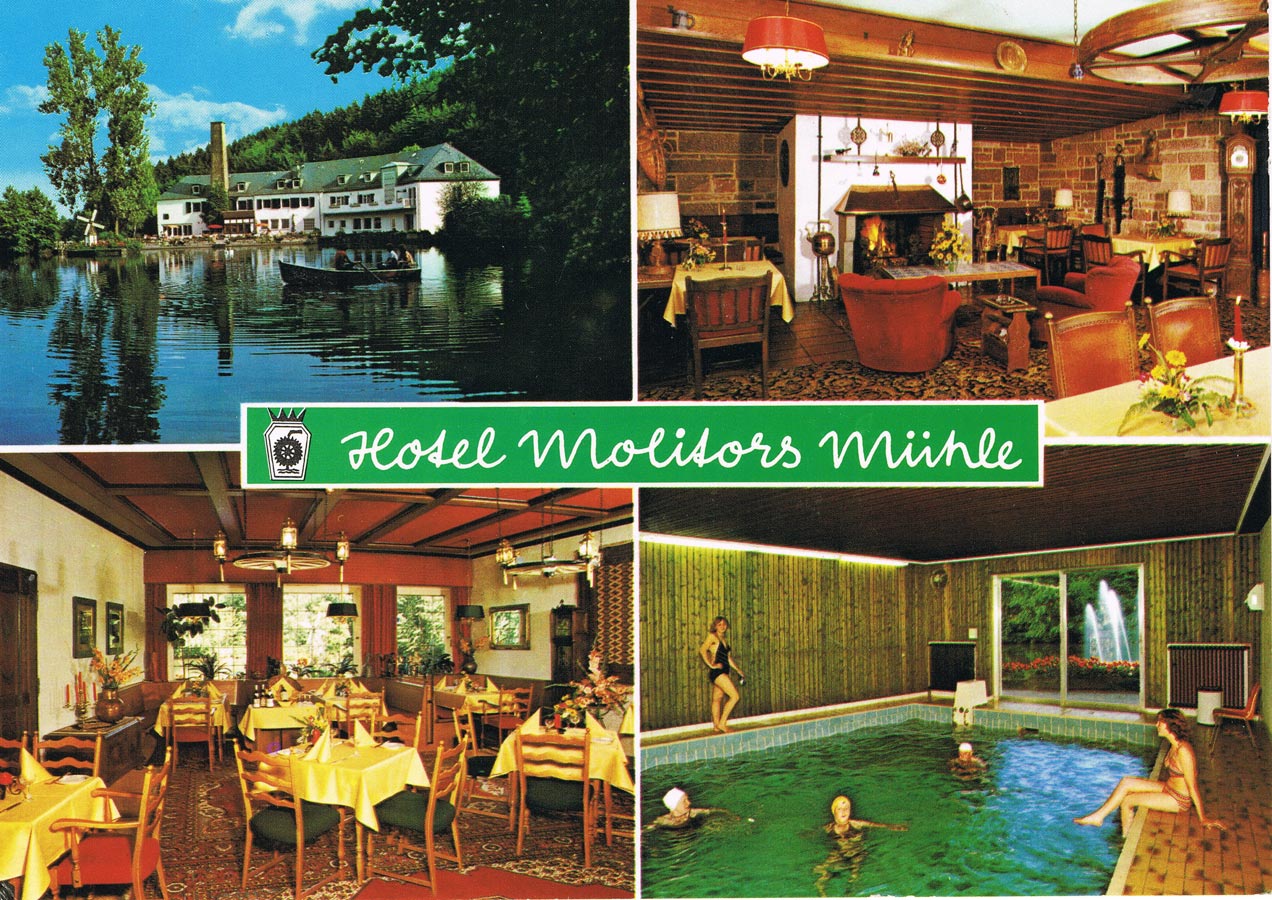

In the summer of 1964, the first guest rooms were booked in the new building. The heating could not yet be switched on because the second part of the new building, in which the heating was planned, was not yet finished (the mill was previously located in this part). So the guests already had a shower and toilet, but not yet hot water. This condition and the board price for three meals per day were communicated to the guests when they reserved the room. Nevertheless, all of the new guest rooms were occupied. The first celebration in the fireplace and wedding room, a double engagement, took place at Easter 1965. From now on we called the guest house, which father Peter and mother Katharina had rebuilt in 1920 at the beginning of the pension, the “old building”.

The second conversion of the new Molitors Mühle

For the third and last major construction phase, the old building was demolished in autumn 1968. The shell was finished by Christmas and the roof covered with cardboard. All rooms were already booked three weeks before Easter. Before Easter, all the craftsmen and ants were in the new building at the same time, almost standing in each other’s way and tirelessly doing the last jobs. All craftsmen finished their work a week before Easter 1968. The swimming pool, the coachman’s room, the sauna and the hairdressing salon were completed in the course of the year. This work was not in the central area and the guest was not significantly disturbed.

In the construction phases from October 1963 to Easter 1969 the hotel was converted and expanded to 23 double rooms and 12 single rooms with shower and toilet, fireplace room, wedding room, coachman’s room, swimming pool, sauna, cosmetic room and hairdressing salon.

You can see all current extensions, modifications, changes when you visit us …